“The phrase pathetic fallacy is a literary term for the attributing of human emotion and conduct to all aspects within nature. It is a kind of personification that is found in poetic writing when, for example, clouds seem sullen, when leaves dance, or when rocks seem indifferent.” [1] It was introduced by John Ruskin to critique what he believed to be the over-sentimentality of the British poets (including Burns, Blake, Shelly, Keats, and Wordsworth) in ascribing emotion to the world around us. “Wordsworth supported this use of personification based on emotion by claiming that “objects … derive their influence not from properties inherent in them … but from such as are bestowed upon them by the minds of those who are conversant with or affected by these objects.” [2]

‘Pathetic’, is an awkward phrase. Having shifted in meaning over the years, it is now more likely to imply someone being ridiculous or inadequate (e.g. ‘you’re pathetic!’) but at the time of Ruskin’s writing, the word was associated more with ideas of pity or poignancy (hence: ‘[sym]pathetic’). Nevertheless, it is clear from Ruskin coupling ‘pathetic’ with the word ‘fallacy’, that he was against the idea he coined the phrase for.

Was Ruskin right? I’m not so sure. Wordsworth’s ideas are powerful and show his recognition of the way we all reflect ourselves onto the world around us. Psychoanalysis seems to support Wordsworth’s ideas, inasmuch as our perceptions of the world are what they are because of what and how we are, while Buddhism goes beyond Freud to suggest that every moment we create our surroundings as a reflection of ourselves, and that to change the world we must change ourselves.

Of course the opposite, that we are affected by our surroundings, is a truism. We even have medical conditions like ‘seasonal affective disorder’ to confirm this, but I wonder if really what we have is a symbiotic relationship with our surroundings, where we are at once affected by and affect the world around us; that we are all part of the same system.

This certainly seemed true today. As soon as I stepped out the door, the autumn gales at once hit me, and at the same time (metaphorically) lifted me into a kind of excitement I’ve always felt in high winds. The leaves really were dancing and within a few feet of the end of my street two young bucks screeched their car into a parking space, not so much in anger and aggression, as in testosterone fuelled exuberance.

On the beach, packs of teenagers ran, almost feral, away from the home hearth-sides of half term to congregate in groups, maybe up to no good, but certainly partaking fully of a world that seemed altogether as fast as the wind.

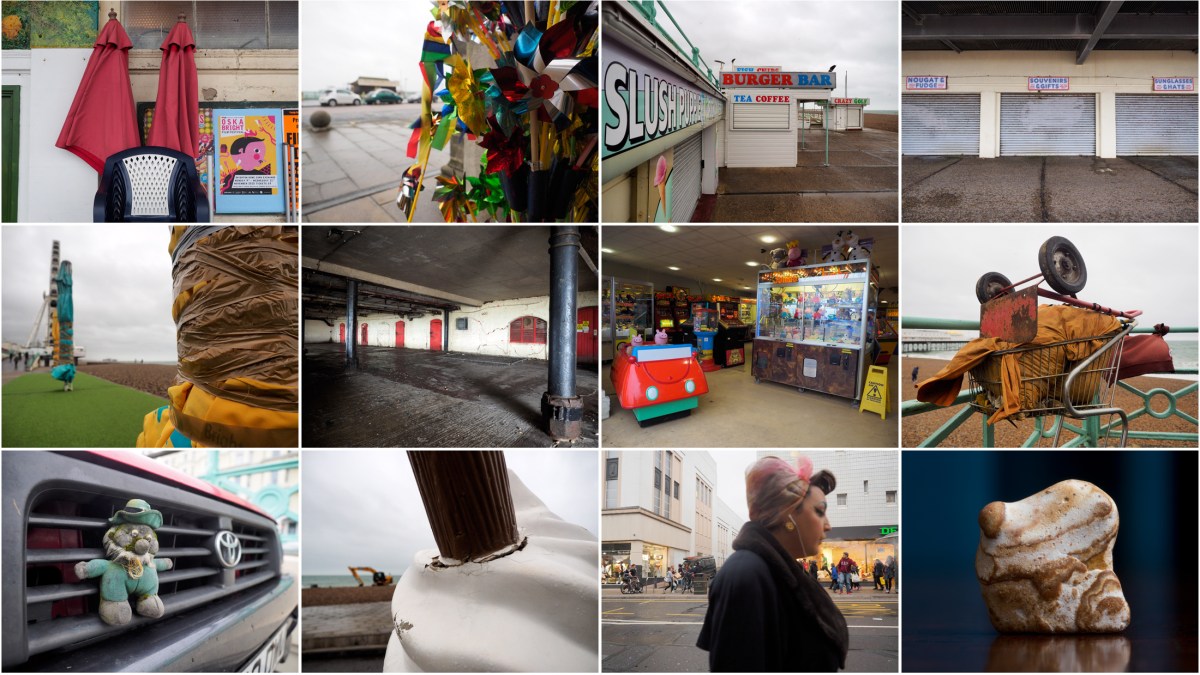

That all this activity was set against a backdrop of a sea-front now more or less closed for the winter (or at least until the sun might come out again one last, last time this season) seemed only to highlight the sense that there was something in the air, and whatever it was, it seemed to call everyone to be a part of it. While café signs were stowed and beach umbrellas trussed like turkeys to prevent them being stolen by the wind, gulls raced with the skies and the beach was dotted with solitaries who, for whatever motive, all seemed to want to lift their arms in the hope of flying too.

We have always sought to personalize the forces around us, sometimes elevating them to the status of Gods. Is it that we need to give them life, or is it that they indeed live and we simply give homage in naming them? And does it matter if this is true or not? The point is more our extraordinary delight as a species to create stories with whatever we find around ourselves, and in so doing to belong to the world rather than be isolated from it, something neither pathetic nor false.

–

[1] wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pathetic_fallacy -requoting from:

Encyclopedia Britannica; Ruskin, John (1856). “Of the Pathetic Fallacy”. Modern Painters,. volume iii. pt. 4; The Penguin Dictionary of Philosophy Second Edition (2005). Thomas Mautner, Editor. p. 455; Abrams, M.H.; Harpham, G.G. (2011) [1971]. A Glossary of Literary Terms. Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 269; Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, Alex Preminger, Ed.

[2] ibid, -requoting from: ‘Wordsworth, William. Knight, William Angus, editor. The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth, Volume 4. W Paterson (1883) page 199’