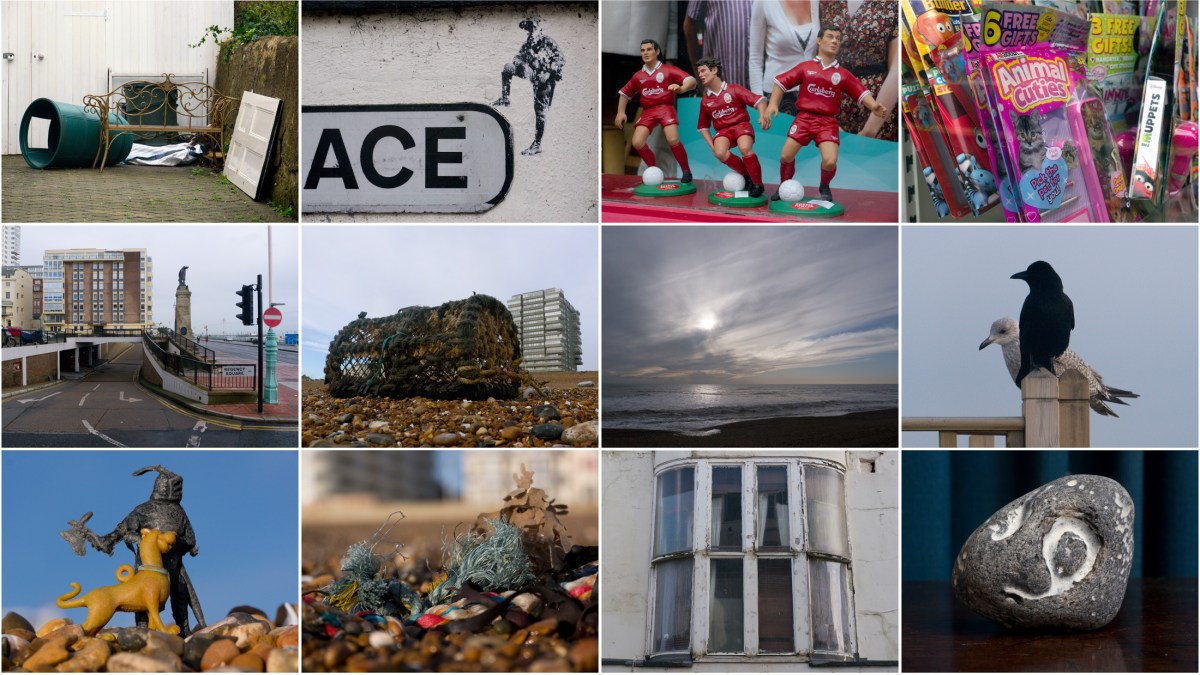

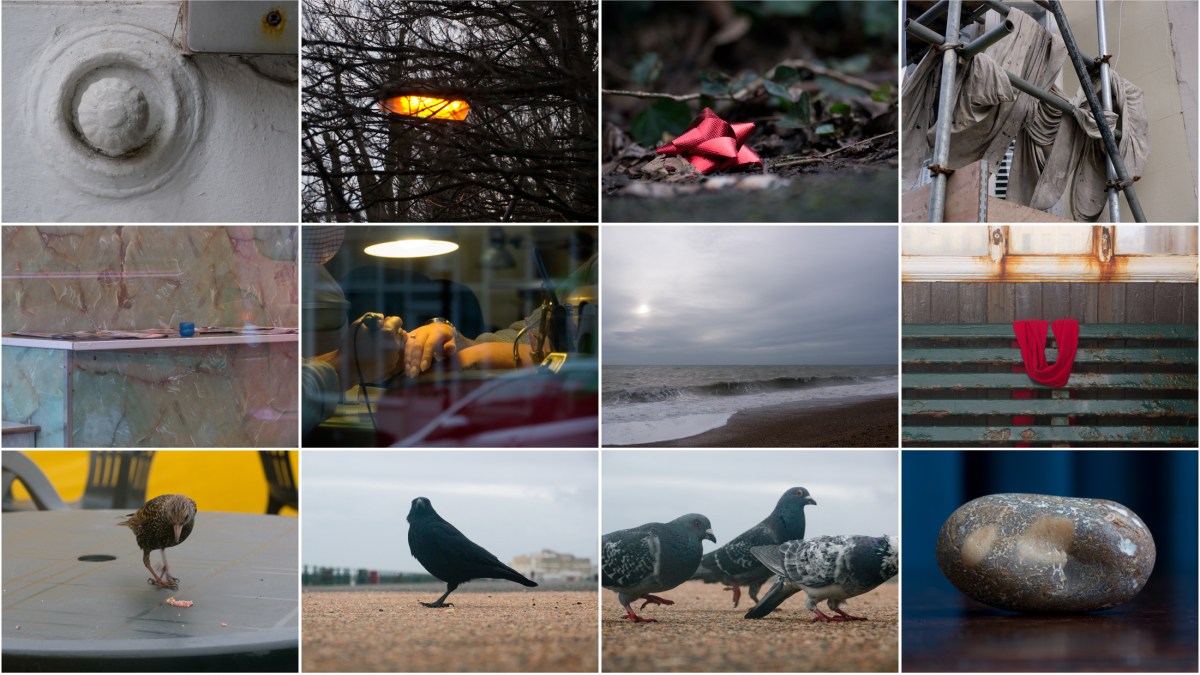

At the café on the sea front where I seem to end up on most days, there are the following: one wagtail, one starling, a family of four crows, around ten pigeons and a population of herring gulls (mainly juveniles) whose number is hard to estimate because they are so mobile. I’m therefore not sure they count as you’d have to see them as passing through rather than truly resident, although there seems to be at least two who have claimed the location as actual territory. These take it in turns to sit on the roof of the café, regularly making more noise than all the other birds put together.

Sometimes the seagulls mob the crows, sometimes the crows mob the gulls. Indeed the gulls often mob each other, seemingly just for the hell of it – and these altercations can, at times, be quite vicious. The pigeons just edge and barge persistently regardless of any other species (including human) or sit on the ground, waiting, like docile cattle, for more food to show up. The starling appears out of nowhere and then vanishes just as mysteriously, while the wagtail spends the majority of its time on the ground, darting hither and thither like a demented clockwork micro-hoover, cleaning crumbs from the cracks between the paving stones.

What gets me though is that despite the fact that they are all after food, when they aren’t actively engaged in foraging they just hang out together, any past misdemeanours seemingly forgotten. And what gets me even more is the disparity in scale between species. This’d be like standing at the bar or waiting at the bus stop with someone three or more times your size and a completely different shape.