Did Cinderella ever forget her roots?

Fairytale endings – Mon 20th July

Did Cinderella ever forget her roots?

Following one of those less than fulfilling conversations down the pub a few nights ago, I’ve been pondering the phrase: ‘couldn’t get a word in edgeways’ and came up with a theory that I was really quite pleased with:

Words have two kinds of existences: utterances, those disembodied things that fly about in verbal exchanges, and the written kind: assembled characters that exist on pieces of paper. Though these latter have physical substance, they add neither noticeable bulk nor thickness to the page they appear on. Words in this context seem entirely two-dimensional.

Based on this reasoning, I’d decided that ‘couldn’t get a word in edgeways’ must apply to mediaeval (and later) masonry and joinery practices whereby, master craftsmen would check to see if a join was good by trying to insert a piece of paper, parchment etc. edgeways into the crack between two abutting surfaces of whatever material. A really good join would be one where, even without the paper, you still couldn’t insert something as lacking in mass as a paperless written word, and therefore if you ‘couldn’t get a word in edgeways’ it meant the join was impervious to outside influence. I reasoned that the phrase as transferred to other situations must have originally been a sarcastic quip based on not being able to penetrate the conversation. Other linguistic metaphors such as ‘watertight alibi’ seemed to back up this idea.

Before publishing this theory I thought I’d better do a bit of online research to check, and immediately came up with the following:

‘A word in edgeways’, or as it is sometimes written ‘a word in edgewise’, is a 19th century expression that was coined in the UK. ‘Edgeways/edgewise’ just means ‘proceeding edge first’. The allusion in the phrase is to edging sideways through a crowd, seeking small gaps in which to proceed through the throng. The phrase ‘edging forward’ exactly describes this inch-by-inch progress. It was first used in the 17th century, typically in nautical contexts and referring to slow advance by means of repeated small tacking movements, as here in Captain John Smith’s The generall historie of Virginia, New-England and the Summer Isles 1624:

After many tempests and foule weather, about the foureteenth of March we were in thirteene degrees and an halfe of Northerly latitude, where we descried a ship at hull; it being but a faire gale of wind, we edged towards her to see what she was.

This practice of ‘edging’ was used with reference to the spoken word by David Abercromby, in Art of Converse, 1683:

“Without giving them so much time as to edge in a word”. (1)

Damn…

(1) http://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/word-in-edgeways.html

The thing about new words is that, regardless of how bad, pointless, or stupid they sound, regardless of convincing etymology or respect for correct usage; once uttered, they exist. True, some will soon fade and pass out of human knowing, but then whole languages disappear once their words have been pronounced for the last time, only a few fragments remaining transmogrified into new words, or occasionally reappearing in obscure papers penned by linguists. Meanwhile other words will rise, apparently from nowhere, and sweep whole countries like an epidemic. Some of us will delight in these novelties, others will howl indignantly at these perceived assaults on convention. Whatever your reaction, ignoring them is as effective as turning your back on a hungry wolf and, on the whole, I think it’s better to keep an eye on them. Those that survive earn their stripes simply through persisting, but some old ‘new’ words were dubious from the start.

Where did ‘mushy’ come from? How long will it last?

I don’t think I know of anyone who actually enjoys doing their end of year accounts but, occasionally, something comes up in the process that stops you searching for yet another displacement activity. The following passage from an insurance company letter, found just after finishing another miniature sculpture made of blu tak, is one such instance:

‘Our standard legal confetti, located on the left of this letter, can be used for information and guidance so you can see how we reference these changes ourselves’

Legal confetti? I have fallen in love with the phrase. It immediately brings to mind ceremonial wigs on hooks in high ceilinged rooms, expansive desks strewn with articles and licences, muffling the surface like snow or, indeed, confetti, or perhaps the baroque language found in every legal document, the whereins and hereinafters; blizzards of verbiage set to confuse any hapless traveller in search of truth, meaning or resolution. The term seemed so right I immediately went in search of its definitive meaning, only to find that there is no such thing; the phrase is a complete invention. This of course delighted me even more.

I then wondered if the word confetti itself might hold a clue to this expanded usage, and found:

Confetti (n.) 1815, from Italian plural of confetto “sweetmeat,” via Old French, from Latin confectum, confectus (see confection). A small candy traditionally thrown during carnivals in Italy, custom adopted in England for weddings and other occasions, with symbolic tossing of paper.

(Online Etymology Dictionary)

and:

…early 19th century (originally denoting the real or imitation sweets thrown during Italian carnivals): from Italian, literally ‘sweets’, from Latin confectum ‘something prepared’, neuter past participle of conficere ‘put together’ (see confect).

(Google)

At first glance, neither of these seemed to offer any hope of meaning in relation to legal practice, but then, thinking about it a bit more I wondered: From the first definition we find the ‘symbolic tossing of paper’ while the second offers ‘something prepared’ and ‘put together’. If we now add the word ‘Legal’ to these meanings, we could arrive at the idea of:

Something symbolic in place of substantiality, prepared specifically for the purpose of offering to participants at moments of legal import.

Or more succinctly, perhaps:

Something purely symbolic to be tossed at clients.

Bingo!

Who is the author of this simple phrase, so light, joyful even, and yet profound? Are they young? Perhaps a bored poet forced into the field out of a simple need to pay the rent, or out of a need to prove to the parents of their beloved that they are more than just a wastrel? Are they someone far older, close to retirement and so wise to the world they no longer fear anything? Whoever they are, their talents are clearly wasted in their current occupation and I look forward to hearing of their emergence as a great story-teller or dramatist one day in the near future. I hope they come across this piece, just so they know they have been recognised and, I hope, understood.

Last night I shared a post I found on facebook comparing the cost of the Greek bailout with the amount used to prop up the banks following the banking crisis a few years ago. The figures were compelling; it also turns out they were fabricated. This is sad because the author had made a good point, and if he had checked his sources he would have found that, while the amount the banks were bailed out by was different to the figures he quoted, it was still colossal in comparison to what Greece needs. Therefore here is some more reliable information:

An article posted in the Guardian on 12th September 2011 (since updated, 20th May 2014) quotes a number of figures based on different factors, but concludes:

“not only has the [UK] government bailed the banks out to the tune of £123.93bn, and at its peak had liabilities for the banking crisis of £1.2 trillion, but the value of its stakes in the biggest banks has plummeted and the interest it is receiving on the loans is relatively small. The interest collected is smaller than that the government pays on its debts, taken out to refinance the banks”

A report published by the USA’s Congressional Budget Office provides several more figures on the American banking crisis. These include:

“By CBO’s estimate, $428 billion of the initially authorized $700 billion will be disbursed through the TARP, including $419 billion that has already been disbursed and $9 billion in additional projected disbursements. The cost to the federal government of the TARP’s transactions (also referred to as the subsidy cost), including grants for mortgage programs that have not yet been made, will amount to $21 billion, CBO estimates…”

Source: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/44256_TARP.pdf

$21bn doesn’t sound very much in comparison to other figures mentioned, but it should be pointed out that this was the actual cost of the bailout, i.e. what the American tax payer won’t ever get back, not the amount of the loans considered necessary, deemed to be $700 billion. It also doesn’t take into account the appalling personal losses through mortgage foreclosures, job losses etc.

The current IMF estimate of the additional loan needed to prop up Greece is 52 billion euros. Of course Greece will need more if it is to finance itself for a full recovery, plus far better repayment terms based on sane levels of economic growth. And consider this: Greece is not a bank, it is a country of just over 11 million people, including children, the old and the sick. Furthermore, the situation Greece is now in is just as much, if not more, to do with the incompetence and near-sightedness (and obsession with propping up banks) of other European Governments, than it is to do with it’s own fiscal inadequacies, yet an entire nation is set to suffer as a result of decisions made by politicians and executives who only seem to have compassion when it comes to their own kind, not others.

Here’s one more quote, from the EU constitution:

“The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail.”

(Article 1-2 The Union’s values. Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe as signed in Rome on 29 October 2004)

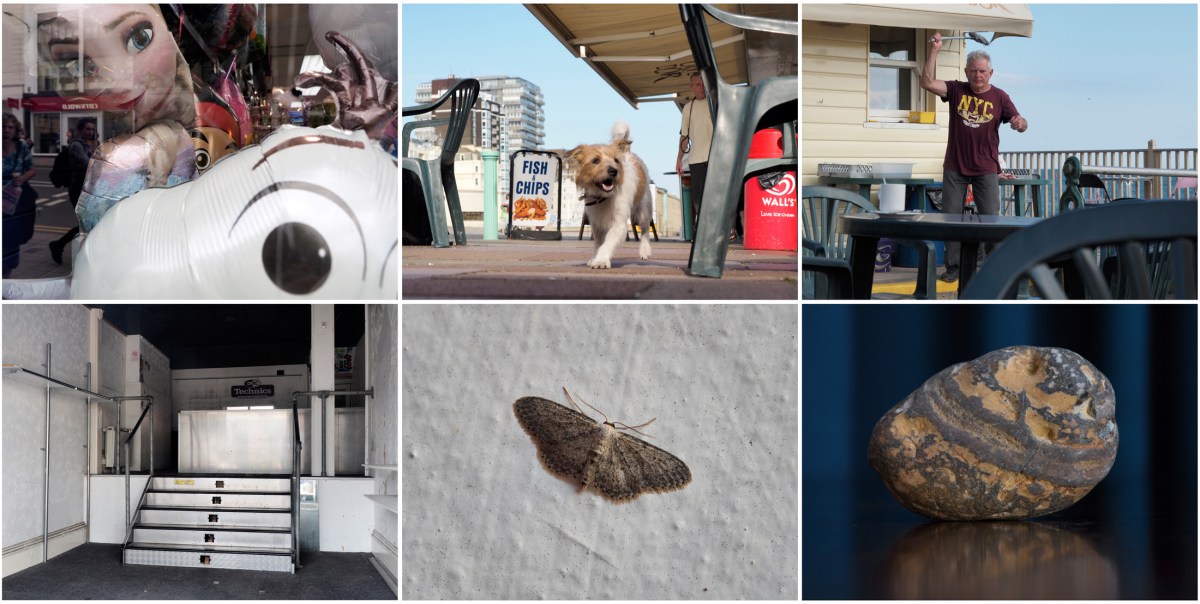

Stones found on one of the tables at the café today, one marked with a price (£3.50) and a name (Alex). Possible theories concerning these objects:

Alex is making his first foray into the world of commerce, selling stones from the beach. While the idea isn’t entirely without merit, it is only likely to appeal to people with stiletto heels who do not want to break them on the pebbles – a limited market. Anyone otherwise so lazy they cannot be bothered to go the extra few feet to gather their own would have been unlikely to have made it as far as the café from their car. If Alex wishes to pursue this venture he should consider a stall by the roadside, although the gift-wrapping is a nice thought.

Alex himself (or possibly herself) has been sold for the measly sum of £3.50. Indeed, judging by the pile of stones and the Kleenex, the vendors might have settled for these instead of cash.

This second theory begs several further questions:

Why has Alex been sold? Is it because Alex had been naughty (Alex must have been very naughty indeed, children usually fetch a much higher price) or because Alex’s parents were hard up and needed to buy some petrol for the car so they could go home? (These things happen, but they’ll be in for a surprise when they try to pay with the rest of the pebbles)

Who to? This particular question holds limitless possibilities, though, given the stones left behind, perhaps as change, it is most likely to be mermaids (mermaids use stones for currency, see entry: ‘Finding treasure – Sun 14th Dec’).

Where is he or she now? Well, that would depend on the correct answer to the above questions.

What do you think?

The man at the café continues his solo crusade to keep the tables a bird-free zone. It’s almost as if he can see through the furniture to the pigeons lurking beneath. In answer, the pigeons have now so finely tuned their sensitivity to danger, that even a raised arm (if it’s the one holding the long handled brush of fear) is enough for them all to take to the air. Of course as soon as his back is turned, the chip-thieves reappear out of nowhere once more…

And the birds also know it’s only him they need worry about. Martin, another member of the café crew has tried similar tactics but to no avail – the pigeons seem to scoff at his efforts. As Martin says: “I just don’t have the authority”. We’ve both discussed the man’s obsession. Is it really necessary? What drives him? Surely he must know it’s as useless as trying to hold back the tides? (Though we’ve both admitted a certain admiration for the fact he seems to be doing just that).

And, what makes his performance all the more extraordinary, is that we have both seen him round the back of the café, away from the tourists, feeding with great care and tenderness the same birds he terrorises in public. It’s as if he has a Jekyll and Hyde split. Or maybe the back of the café is the gateway to a parallel universe where all of us have opposite personalities to the ones we possess in this universe. Or maybe it’s more mundane; maybe he’s just trying to teach the birds that it’s ok to eat, just not on the café tables, that he has a job to do and the tourists must be left in peace when they are eating. Maybe he is actually a keen ornithologist who, through some cruel quirk of fate has founds himself with a job that demands this behaviour and as a result every night he goes home and weeps silently into his pillow at the horror of what he has to do, and maybe he feeds them out of guilt: a kind of penance to make up for his public despotism.

We just don’t understand. However, we have both also spotted that, despite the fact that he seems to have a very good aim – he’s never once hit a tourist – he’s also never once hit a bird either.

“It is as reasonable to represent one kind of imprisonment by another, as it is to represent anything that really exists by that which exists not.”

Daniel Defoe

There are various accounts relating how England (and Caledonia) for a while came to be called Albion. The two most prominent date to Roman times: that on a clear day from northern Gaul the sight of the white cliffs of Dover gave rise to the belief that this country was entirely white; or that this was the name given to the country by Julius Caesar following his first attempt to invade our shores and upon espying these cliffs for the first time. Both of these accounts cite that the word ‘Albion’, also originally favoured by the Greeks as the name for our island, came from the root ‘alb’ in both Greek and Latin meaning ‘white’, hence also: albatross, albedo, albino, album, albumen etc… and would have therefore been appropriate as a simple description.

Personally I like this theory, one that I’ve known about, and believed, for a long time. I can imagine Caesar at the prow of his trireme espying the cliffs of Dover (or whatever they were called then) for the first time, his cape billowing in the wind, exclaiming: “Blimey, they’re white!” and several people who I have talked to about this have cited accounts by Tacitus and Pliny the Elder, which they claim back up these theories.

However, in researching today’s entry, not only have I found no evidence that either of these Roman historians used the word when relating the story about Caesar, but also I’ve found out its all a bit more complicated linguistically too. Here’s the etymology according to Wikipedia:

“The Brittonic name for the island, Hellenized as Albíōn (Ἀλβίων) and Latinized as Albio (genitive Albionis), derives from the Proto-Celtic nasal stem *Albi̯iū (oblique *Albiion-) and survived in Old Irish as Albu (genitive Albann). The name originally referred to Britain as a whole, but was later restricted to Caledonia (giving the modern Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland, Alba). The root *albiio- is also found in Gaulish and Galatian albio- (“world”) and Welsh elfydd (elbid, “earth, world, land, country, district”). It may be related to other European and Mediterranean toponyms such as Alpes and Albania. It has two possible etymologies: either *albho-, a Proto-Indo-European root meaning “white” (perhaps in reference to the white southern shores of the island, though Celtic linguist Xavier Delamarre argued that it originally meant “the world above, the visible world”, in opposition to “the world below”, i.e., the underworld), or *alb-, Proto-Indo-European for “hill”.”

So now I’m left only able to say that maybe it was, maybe it wasn’t anything to do with the chalk cliffs, or Caesar. This is a bit irritating. On the other hand it’s an ill wind… I can now see many happy hours ahead of me trying to find out what a ‘Proto-Celtic nasal stem’ is instead.

First sighting in Hove of ‘viator facies similem nephropidae’ (Lobster-faced tourists) somewhat late in the year. Possible reasons for divergence from previous seasons:

I reckon I could get a research grant for this kind of quality thinking.

Notes: Correct Latin terminology arrived at via Google translate