“Platonic dialectics of large and small do not suffice for us to become cognizant of the dynamic virtues of miniature thinking. One must go beyond logic in order to experience what is large in what is small.”

Gaston Bachelard, ‘The Poetics of Space’

“Platonic dialectics of large and small do not suffice for us to become cognizant of the dynamic virtues of miniature thinking. One must go beyond logic in order to experience what is large in what is small.”

Gaston Bachelard, ‘The Poetics of Space’

The music bar on the seafront has not failed in its promise to put on live music every day this summer (apart from days when it’s really pissing it down). It hasn’t always been great music, most of the content being cover songs sung to backing tracks by young hopefuls. Nevertheless it’s quite an accomplishment. The venue has also been a boon for my own content, being a magnet for most of the visiting hen parties, stag do’s, drunks and, occasionally, the police.

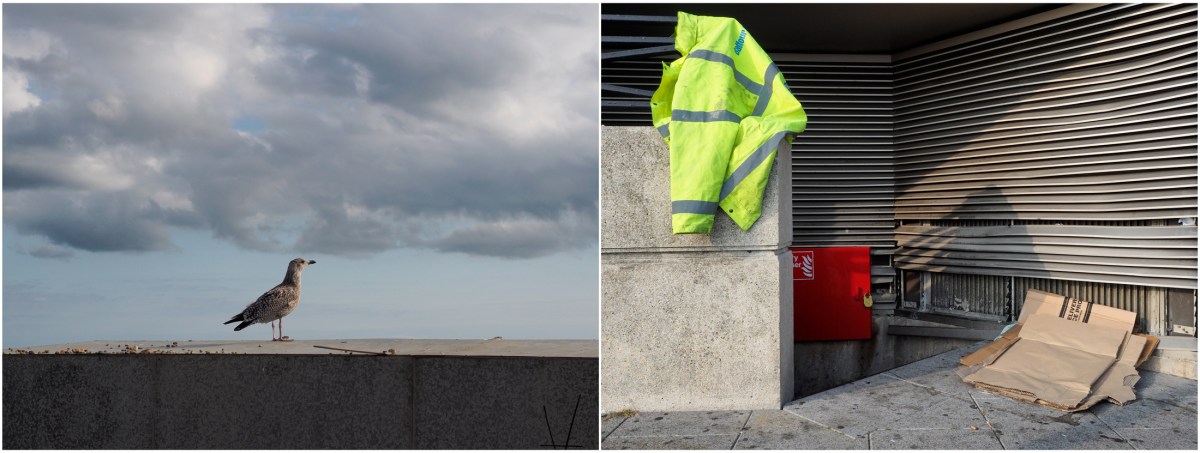

One of the regular performers, someone who’s appeared in the background of several of my previous posts, is a woman in her mid twenties. She’s got a good voice and belts out all the standards with great enthusiasm and aplomb. But now it’s the end of the season and on a bleak day like today, the sea front is deserted. Yet there she is still, singing at the top of her amplified voice as ever, to absolutely no one.

Or do I count? I tried smiling sympathetically at her as I walked past, in a gesture of camaraderie for those of us who still loiter by the deserted shore, but she looked straight through me, perhaps to the sequinned crowds of her minds eye.

The encounter brought to mind George (Bishop) Berkeley’s famous quote: “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” Since thinking of this I have wondered if the same might apply to nightclub singers.

“I have checked my memory with Doris, who also knew Haldane well, and what he actually said was: “God has an inordinate fondness for beetles.” J.B.S.H. himself had an inordinate fondness for the statement: he repeated it frequently. More often than not it had the addition: “God has an inordinate fondness for stars and beetles.” …Haldane was making a theological point: God is most likely to take trouble over reproducing his own image, and his 400,000 attempts at the perfect beetle contrast with his slipshod creation of man. When we meet the Almighty face to face he will resemble a beetle (or a star) and not Dr. Carey [the Archbishop of Canterbury].”

(Kenneth Kermack discussing one of the most famous quotes of his friend, the geneticist and evolutionary biologist: J. B. S. Haldane, as requoted by Stephen Jay Gould in his article: ‘A Special Fondness for Beetles’ in the January 1993 issue of Natural History (Issue 1, Volume 2), again reprinted on p. 377 of his book ‘Dinosaur in a Haystack: Reflections in Natural History’)

Actually, the above line of reasoning only works if we assume God is a narcissist. Otherwise, for all we know, he (or she, it, or they) may well look like Dr. Carey the (then) Archbishop of Canterbury. J. B. S. Haldane himself was a bit of a dandy.

If you ask any child, up to the age of about six, to paint you a picture of rain, they’ll have no problem doing so. The patterns of slashes and spots they will give in response are almost as much a part of infant iconography as lollipop trees and houses with chimney smoke like springs. But I was thinking today, while trying to avoid getting soaked, that I couldn’t remember much in the way of examples of grown ups painting downpours.

Ok, I’m going to have to qualify this a bit. Japanese art has a rich tradition of representing rain, but what about the west? Looking back through our own art history, most only show rain as either atmospheric (Turner, Monet, impressionism) or in terms of its effects and paraphernalia: rainbows, dark threatening clouds, umbrellas, puddles, shiny streets, etc. storm damage and thrashing trees (Ruisdael, Dutch painters). but not much in terms of depictions of recognisably distinct drops. The only exceptions I can find are a few mediaeval paintings showing rains of fire and blood as part of the apocalypse or in the wake of Hailey’s comet (and I don’t think blood and fire counts). Even representations of Noah’s flood seem to be absent of actual falling droplets.

I can only think of three artists: Sickert, Hockney and Alex Katz, who’ve done so. All of these painters worked relatively recently, a long time after Japanese woodblocks had become widely known in the west, and also, after the development of photography to a point of technical advancement able to capture at least streaks of water in its fall downwards.

So how come children have no problem with painting and drawing rain, but adults, at least in the west, do? Is there a point in our development when we forget how to do such simple things?

Goethe’s colour theory differs in a number of respects to Newton’s writings on light. One such distinction lies in Goethe ascribing aesthetic values to the colours of the rainbow, thus: magenta (purpur) and red (rot) are seen as ‘beautiful’ (schön); orange (gelbrot) as ‘noble’ (edel); yellow (gelb) as ‘good’ (gut); green (grün) as ‘useful’ (nützlich); blue (blau) as ‘mean’ or ‘common’ (gemein); and purple (blaurot) or violet (violett) as ‘unnecessary’ (unnöthig). For a while now I have been curious as to why Goethe considered ‘violett’ and ‘blaurot’ to be ‘unnecessary’ and whether this choice of words itself had an effect on the subsequent development of artistic practice. Following some digging around, I ask you to consider the following:

The word ‘magenta’ didn’t exist as a colour term at the time of Goethe’s writing his ‘Theory of Colours’ (original German title’ Zur Farbenlehre’ published in 1810). Indeed the pigment was only invented in 1859 and so the word ‘magenta’ has only been used in more recent translations of the work, as the correct colour to be found next to red but before violet on the colour wheel. In his book the word Goethe used for this colour is ‘purpur’ looking, to English eyes, remarkably like purple. At the other end of the spectrum, Goethe’s words: ‘violett’ and ‘blaurot’ are both close approximations of, yes, purple. To labour the point, on modern colour wheels violet (or purple) and magenta are next to each other, but in Goethe’s wheel, ‘blaurot’ and ‘purpur’ are adjacent. It may be that, due to the quality of pigments available at the time, and lacking the differentiation provided by magenta as a pigment, Goethe saw these colours as actually being too similar, one therefore becoming to him unnecessary.

J M W Turner was heavily influenced by Goethe’s ‘Theory of Colours’, the ideas it promoted having such an effect on the artist that he made reference to the work in the titles of several of his paintings. Turner’s lectures on colour, being delivered around 1827, suggest that he might have been familiar with the book at that time, prior to its English translation in 1840. Interestingly, Turner ignored purple in his own colour wheels produced for these lectures, removing the hue completely from the diagrams and giving half of the spectrum over to yellow in compensation.

Furthermore, you never see purple in any of Turner’s paintings. According to some sources, this is because he simply hated the colour, but what if Turner’s reason for this act of chromicide was due to his incomplete understanding of a yet to be properly translated book, in which the word ‘unnecessary’ took on a greater significance than Goethe had intended? It should also be noted that Turner died seven years before Magenta was first produced.

Did a simple mistranslation affect the entire oeuvre of one of England’s greatest artists? Whatever the reason, thank heavens for that. I too detest purple, with a vehemence brought about by years of teaching art students who, whenever they want to be seen as ‘self-expressive’ use buckets of the stuff usually swirling around in shapes that, diplomatically, can only be described as mystical orifices. Can you imagine a roomful of purple, violet and magenta Turners? The thought makes me feel quite sick.

Why is lemon yellow called ’lemon’ yellow? I have a lemon in front of me and it looks decidedly more like cadmium or chrome yellow in colour. Grapefruits are closer to lemon yellow so why don’t we say ‘grapefruit yellow’? And come to think of it, ginger isn’t ginger, is it?

In his novel ‘The turn of the screw’, Henry James describes the special horror of beholding a ghost in daylight (see entry for Tues 17th Feb). The spirits should belong to the hours of darkness, the time when we should be sleeping, when we let go of the rules of logic. Seeing them beyond these confines adds further to the terror of their encounter. Not only are they there, but they have invaded our territory.

The boundaries of darkness are not the only ones we erect to keep the other world at a safe distance. When we imagine the supernatural, they not only belong to the hours of darkness, but we envision them against a backdrop of ancient buildings, ruins, graveyards, behind the scenes at the fairground, the depths of the woods and the wild moors; places we shouldn’t be. I have wondered if we worship our gods in Churches and temples, perhaps as much to keep them safely out of our everyday lives as to honour them with sacred sites.

The horror of the 1982 film ‘Poltergeist’ while transgressing these boundaries by placing the action within a normal suburban setting, at the last moment gives into convention by revealing the cause of this malevolent infestation: that the housing estate where the story takes place is the site of an old graveyard, and the spirits are, therefore, only reclaiming their land. As the last few remains of the housing development are swallowed up by the ground, paradoxically we know that normality has been restored.

Zombie movies, while more often set in the realm of the everyday, and as much in daylight as at night, still fall back on convention: so what if they can eat our brains or turn us into one of them with a scratch or bite, everyone knows we can finish off the walking dead by shooting them in the head. In this respect Zombie movies are more like alien stories: all of these unknowns have weaknesses we can overcome through courage and technology.

So, what about the idea of suburban ghosts? There are films and stories based on these (e.g. the 70s television series ‘Randall and Hopkirk (deceased)’; ‘Truly Madly Deeply’: ‘The Sixth Sense’; ‘Ghostbusters’…) but in each of these cases the ghost is anything but sinister and, more likely than not, either a comic or tragic figure. Carlos Castaneda perhaps comes closest to the idea of the strangeness of the other existing in our own surroundings when he describes a conversation between himself and Don Juan, the Yaqui sorcerer at the centre of his narratives. While walking through a busy street, Don Juan tells Castaneda that most of the people around him are ghosts and that they walk beside us in every situation. Yet this story still has no real horror in it, perhaps because, if this is the case, how can you be terrified of something that is such a part of normal life?

Contrary to popular belief, dogs are not descended from wolves. Rather they share a common ancestry, diverging as species between 27,000 and 40,000 years ago. Nevertheless wolves and dogs have very similar mitochondrial DNA (differing by about 0.2%) and are therefore able to interbreed. This accounts for the resemblance some varieties of dog have to wolves, e.g. Huskies, Alsatians. However, it does not explain how Dachshunds happened. Their name may be a translation from the German, meaning ‘badger hound’ but I don’t reckon they just ended up that way as a result of a staple diet of badgers necessitating the development of shorter legs (to go down holes in the ground) via natural selection.

Only a day later and the only signs of Pride having happened are a few leftover shop displays and a larger number of multicoloured feathers than usual to be found in gutters around town. The ordinariness is something of a relief, though it’s taking me a while to adjust from photographing human carnage to refocusing on quieter things. Mattresses continue to come and go, but most worthy of note, alongside the broken furniture left by the bins, I’m now beginning to find piles of school textbooks. Is this something to do with the approaching A-Level results, due to be released in only a few days?

Anyone leaving school would have done so a few weeks ago and I was surprised not to see more of this paraphernalia appear in the streets then, but maybe it takes the impending receipt of a grade to trigger this desire to put away childish things? Go and get a proper job, or not; have a family, or not; go to university, or not, what are you going to make of yourself? It seems unfair that people who are still only children are pushed to answer these impossible questions. Perhaps it’s because so many adults cannot, that we demand it of them instead.

After a few days, we began to wonder where all the junk shops were. Stopping in a bookshop to get a better map of the city, we asked the owner if he could point us in the right direction, extending the question to include flea markets, antique dealers; anything of that kind really? He replied that he’d never come across them in the city. I have several theories about this but I’m not airing them here. It’s not a good idea to make assumptions about a country you have such limited experience of. Nevertheless, the absence seems significant.