The last time I came across a Jugganath was many years ago in a temple back yard in Chennai, so it was a treat to see one on Hove prom today, pulled by a large gathering of Hare Krishna devotees. Jugganath is the name of a particular form of Vishnu, but we are more familiar with the word through its association with the huge wooden chariot that transports the deity. This name, anglicised to ‘Juggernaut’ has become synonymous with not only monstrous trucks, but anything vast and relentless. Even without the rather fanciful stories brought back from India by early European visitors, of religious fanatics throwing themselves in ecstasy under the wheels of this lumbering beast, it’s not hard to see this giant as being unstoppable.

Juggernaut isn’t the only word from the Indian subcontinent to have been incorporated into English. Quite apart from those you’d expect, like the mystical: Karma and Nirvana, or those words associated with food, like: Basmati and Dhal, there are plenty more. Here are a few favourites of mine:

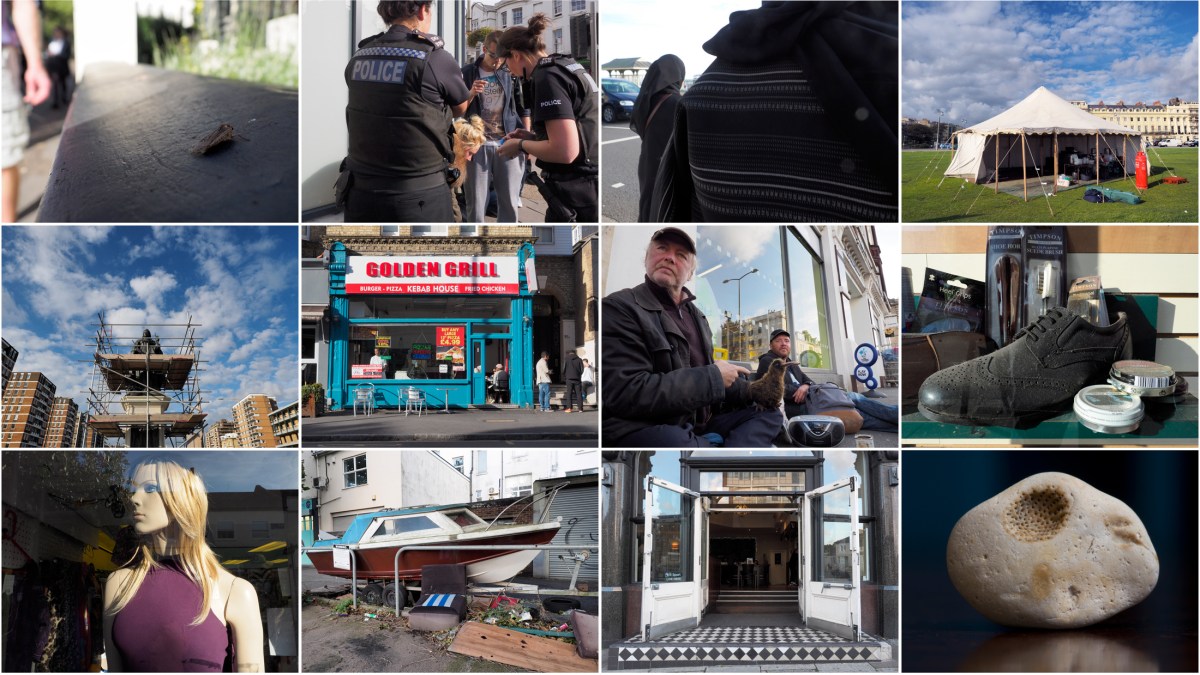

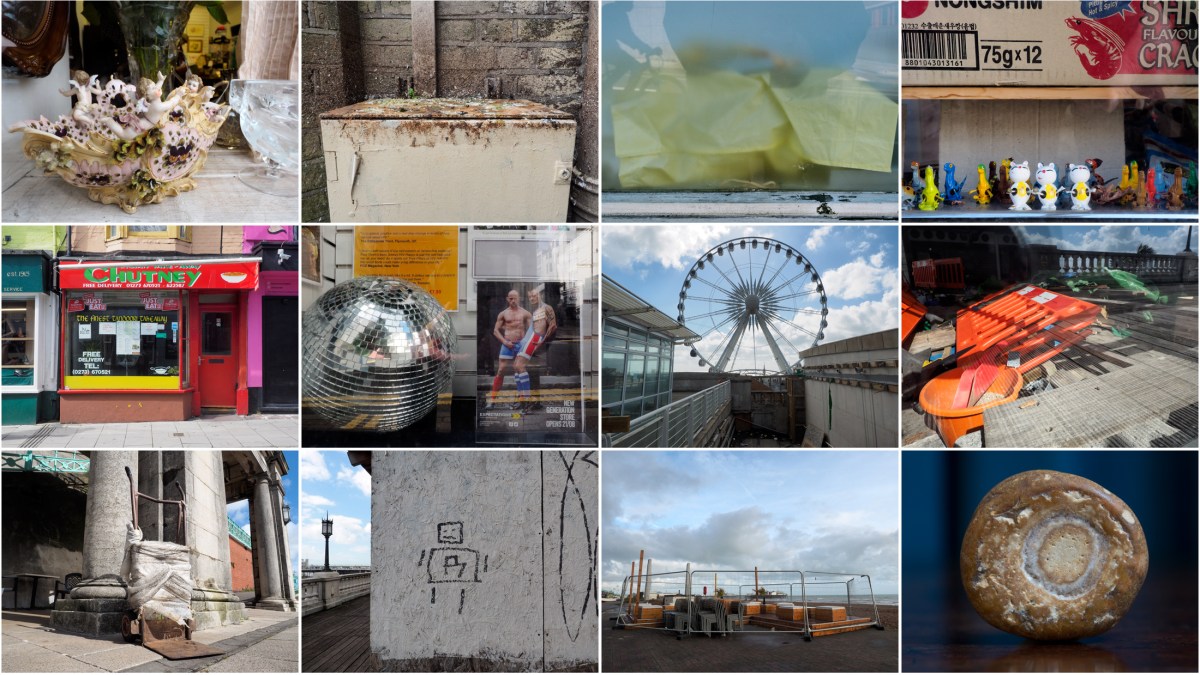

Bangle, Beryl, Blighty, Bungalow, Chutney, Cushy, Dekko, Jungle, Karma, Loot, Palaver, Pundit, Pukka, Pyjamas, Sorbet, Shampoo, Thug, Toddy, Typhoon, Veranda.

Oddly enough though, ‘Curry’ is not Indian in origin. Well, I say that, the subject is still hotly debated. But while on the one hand, the word has been suggested as being an Anglicisation of the Tamil word ‘Kari’ (கறி) meaning ‘sauce’, or, according to other sources, ‘gravy’ and ‘stew’ – the word in this form first encountered in the mid-17th century by members of the British East India Company – on the other hand, the word ‘Cury’ is known to be Middle English in origin, one proof of this being that it is one of the title words in the first English cookbook: ‘The Forme of Cury’ written in the late 14th Century during the reign of Richard II.

Or maybe in a fabulous instance of synchronicity the word arose, in relation to cooking, in both places at once? Who knows? But I would suggest that if you go into a restaurant in India asking for a curry, you’ll get a very old fashioned look from the catering staff.