Vampire temperance society annual day out

Short treatise on Bram Stoker’s legacy – Fri 15th May

Vampire temperance society annual day out

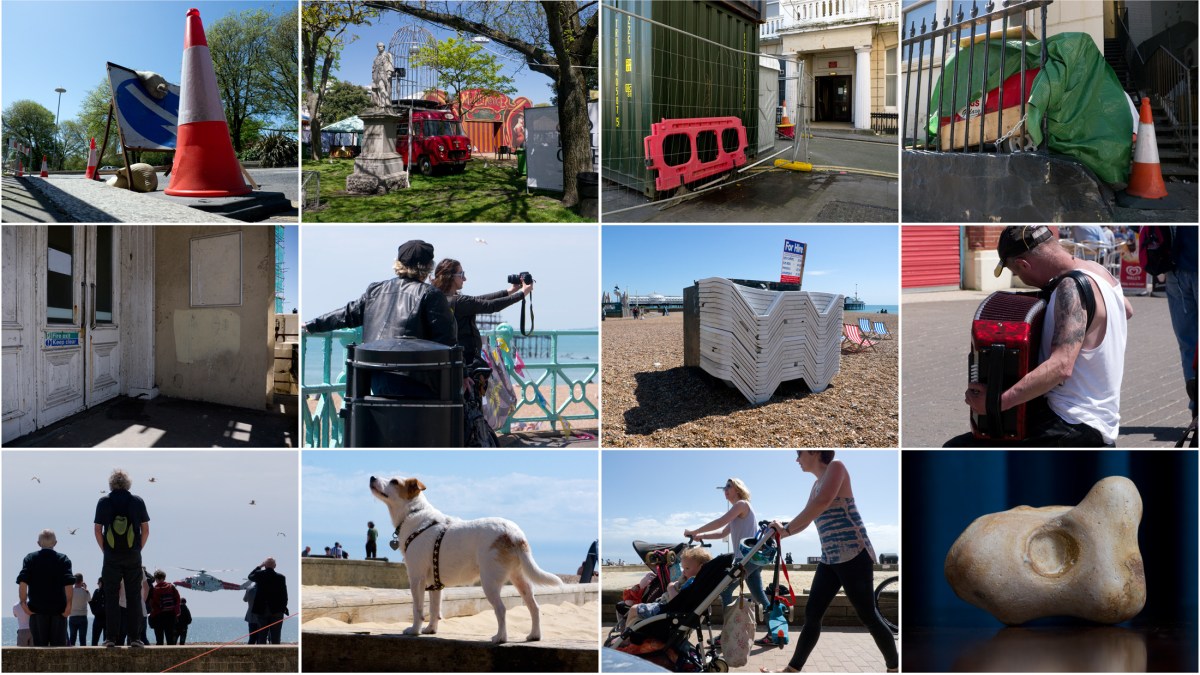

Today the rain is coming down in sheets but, regardless, I am still going OUT. I know that in this weather all the outdoor cafés will be closed, and I want to be outdoors, but luckily I’m prepared for this with a new toy: a thermos flask. Now, ok, this doesn’t exactly sound like the highlife, but in a world of shopping malls, virtual reality, apps and skinny lattes, sitting in one of the covered shelters on the seafront in the pouring rain with a thermos of tea has, in my opinion, become the new exotic.

And I’ve brought some stale bread to feed the birds…

Of course when I get to the sea front there are no birds anywhere to be seen, but just because you can’t see them, doesn’t mean that they haven’t spotted you. I find a shelter out of the wind, put the camera on the ground pointing in roughly the right direction, being careful to avoid drips and splashes, and then I toss the first few morsels onto the sodden pavement.

Within seconds the first bird turns up: I’m delighted to see it’s the crow, someone I haven’t seen for a while. Then a seagull lands, followed by a pigeon who walks nonchalantly but purposefully into view. I now throw quite a lot of bread out at once so every bird should get at least something.

Several more pigeons arrive and then, out of nowhere, a whole pack of seagulls. The crow quickly makes his exit; he’s already been lunged at, so now it’s just the pigeons and gulls. You’d think the gulls would have the advantage, being twice the size of any other bird here and certainly a lot more aggressive, but in fact the pigeons are getting a better deal because they are less nervous of human proximity. Also, the gulls are now fighting among themselves. One in particular, clearly the biggest and very territorial, is too nervous to get close enough to take what’s on offer, but instead of overcoming its fear, decides instead to attack any other bird that looks like its going to get something to eat. It’d go for the pigeons too but attacking them would also mean getting too close to me. This is clearly upsetting the seagull. The pigeons remain oblivious of this looming wave of spite but then, oh for god’s sake, one really big pigeon has seen all the others gathered here and decided, not to join in the free meal, but that this is an opportunity to have sex with a whole harem of potential playmates. This does not go down well with the rest of the pigeons and what I’m looking at now is beginning to resemble the decline of Rome.

Then, to cap it all, while all this attempted sex and fighting is going on a dog turns up and straightaway eats all the bread before its master calls it away.

I can only describe the following silence as loaded.

Once I’m home and have downloaded the photographs of today’s events, I too am a bit disappointed to find I’ve had the camera on the wrong settings and that most of the photos are pretty much unusable (apart from the one pictured, which needed a lot of rescuing). But, given I’ve just seen the rise and fall of any number of civilizations played out in front of me, re-enacted by birds and compressed into only about ten minutes, I’m not really complaining. The thermos flask worked pretty well too.

“Is he here?”

“Noooo!”

“Is he over here?”

“Noooo!”

“What about under here?”

“Noooo!”

“Is he in the wardrobe?”

“Noooo!”

“I don’t think he’s here at all”

“HE’S BEHIND YOU!”

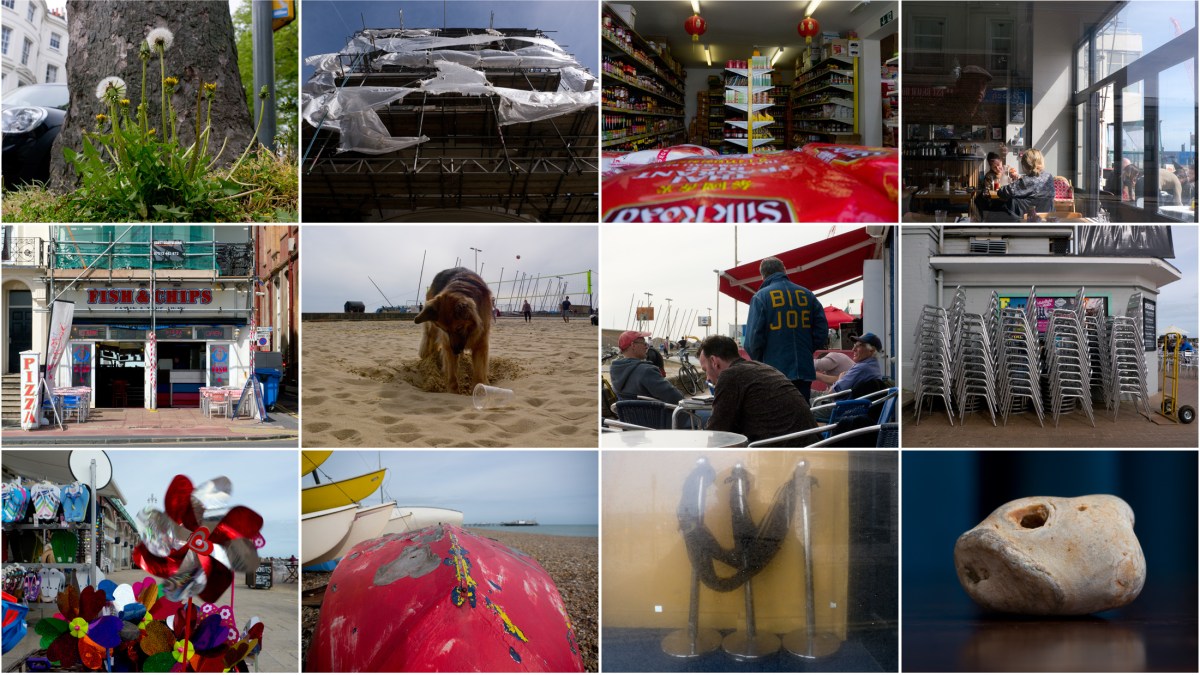

There are various accounts relating how England (and Caledonia) for a while came to be called Albion. The two most prominent date to Roman times: that on a clear day from northern Gaul the sight of the white cliffs of Dover gave rise to the belief that this country was entirely white; or that this was the name given to the country by Julius Caesar following his first attempt to invade our shores and upon espying these cliffs for the first time. Both of these accounts cite that the word ‘Albion’, also originally favoured by the Greeks as the name for our island, came from the root ‘alb’ in both Greek and Latin meaning ‘white’, hence also: albatross, albedo, albino, album, albumen etc… and would have therefore been appropriate as a simple description.

Personally I like this theory, one that I’ve known about, and believed, for a long time. I can imagine Caesar at the prow of his trireme espying the cliffs of Dover (or whatever they were called then) for the first time, his cape billowing in the wind, exclaiming: “Blimey, they’re white!” and several people who I have talked to about this have cited accounts by Tacitus and Pliny the Elder, which they claim back up these theories.

However, in researching today’s entry, not only have I found no evidence that either of these Roman historians used the word when relating the story about Caesar, but also I’ve found out its all a bit more complicated linguistically too. Here’s the etymology according to Wikipedia:

“The Brittonic name for the island, Hellenized as Albíōn (Ἀλβίων) and Latinized as Albio (genitive Albionis), derives from the Proto-Celtic nasal stem *Albi̯iū (oblique *Albiion-) and survived in Old Irish as Albu (genitive Albann). The name originally referred to Britain as a whole, but was later restricted to Caledonia (giving the modern Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland, Alba). The root *albiio- is also found in Gaulish and Galatian albio- (“world”) and Welsh elfydd (elbid, “earth, world, land, country, district”). It may be related to other European and Mediterranean toponyms such as Alpes and Albania. It has two possible etymologies: either *albho-, a Proto-Indo-European root meaning “white” (perhaps in reference to the white southern shores of the island, though Celtic linguist Xavier Delamarre argued that it originally meant “the world above, the visible world”, in opposition to “the world below”, i.e., the underworld), or *alb-, Proto-Indo-European for “hill”.”

So now I’m left only able to say that maybe it was, maybe it wasn’t anything to do with the chalk cliffs, or Caesar. This is a bit irritating. On the other hand it’s an ill wind… I can now see many happy hours ahead of me trying to find out what a ‘Proto-Celtic nasal stem’ is instead.

‘He ordered the messenger to continue to the banks of the above-mentioned river Clyde with a fishhook, and to cast the hook into the stream and bring back to him immediately the first fish that was baited and drawn out from the waters. The messenger fulfilled what the saint said and delivered into the presence of the man of God the fish he had captured, which is commonly called a salmon. Kentigern requested that the fish before him be cut and gutted, and he discovered the above-mentioned ring in it. And at once he sent it to the queen by that same messenger. When she saw it and took it back, her heart was filled with joy and her mouth with exaltation and thanksgiving. Her grief turned into joy and the expectation of death into the festivities of praise and deliverance. Therefore, the queen rushed into the midst of everyone’s eyes and returned the ring that had been sought by the king.’

From ‘The Life of Kentigern’, by Jocelyn, a monk of Furness (12th century)

Translation by Cynthia Whiddon Green

http://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/Jocelyn-LifeofKentigern.asp

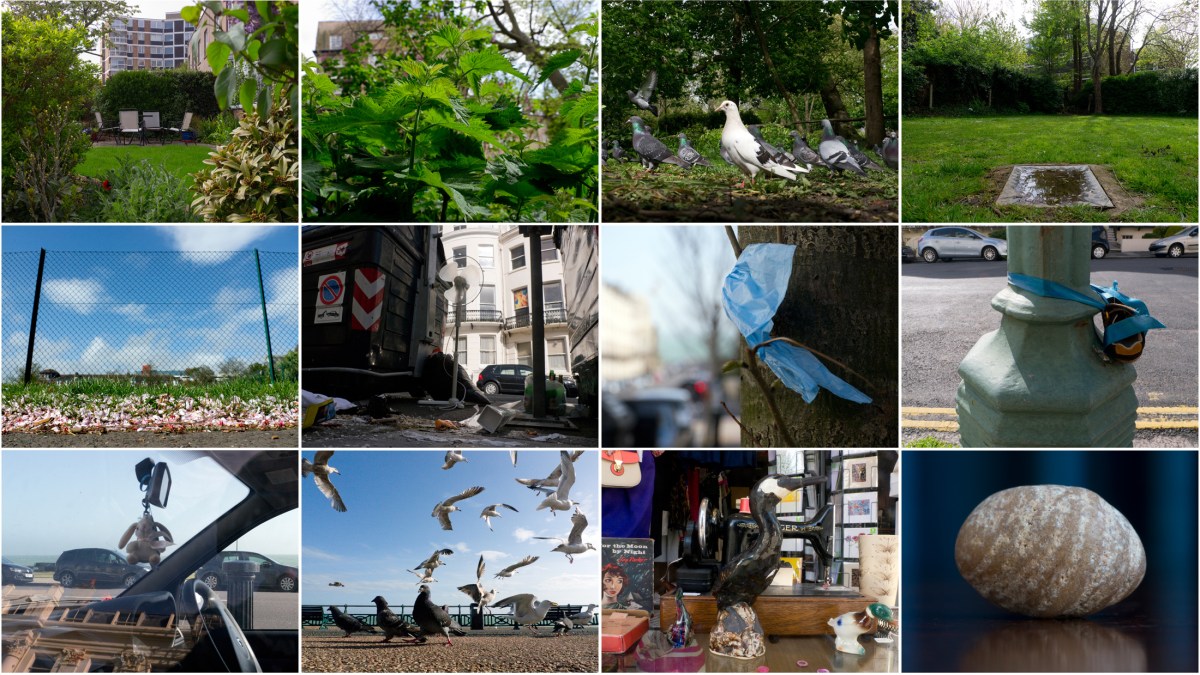

First sighting in Hove of ‘viator facies similem nephropidae’ (Lobster-faced tourists) somewhat late in the year. Possible reasons for divergence from previous seasons:

I reckon I could get a research grant for this kind of quality thinking.

Notes: Correct Latin terminology arrived at via Google translate

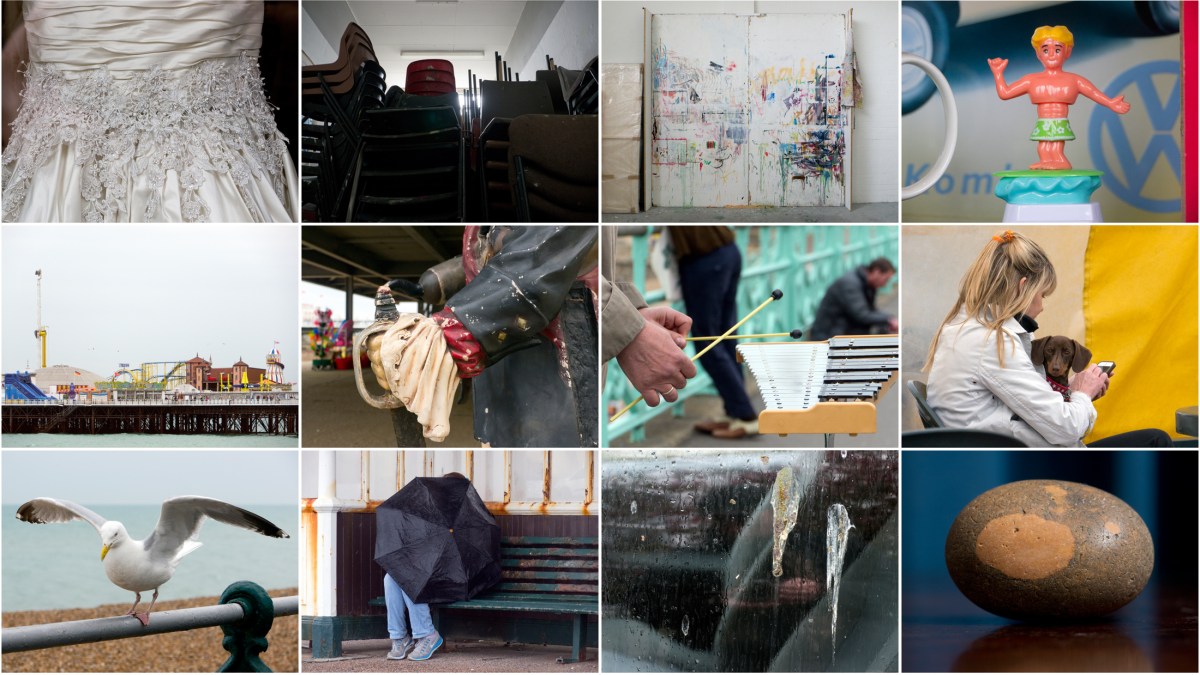

Several theories have been floated regarding the sensation I described yesterday*. These range from out of body experiences, to comments that I was under the influence of various artificial stimulants. One suggestion: ‘somatic symptom disorder’, does come close – after all, it was certainly ‘all in [or on] my head’ – but only because in reality a seagull had landed on mine in the mistaken belief that it would provide a handy platform from which to eat the (my) aforementioned prawn sandwich.

I suppose it could have been worse. As mentioned in my post of 19th March, Aeschylus the Greek Tragedian was killed outright when an Eagle mistook his head for a rock and dropped a tortoise on him from a great height. At least I (and my sandwich) came out of the encounter unscathed, and it is some comfort to know that now, somewhere on the seafront, a seagull has learned that certain kinds of large pebble will shout “fuck off you little sod!” when landed on.

–

*mainly because facebook truncated my post again, removing the (admittedly somewhat obscure) punchline.

Today I discovered an entirely new sensation. Soft and clammy overall but quite sharp in points around the edges, the feeling was confined to my head and was only fleeting, lasting maybe a second, followed by a sudden down-draft of air. Despite, or perhaps because of its briefness I was completely startled, unable to make sense of what I’d felt until it had passed and the cause had more or less disappeared. I don’t think I’ve ever known anything like it.

If you want to experience something similar, I would first recommend shaving your head to guarantee contact unadulterated by any intervening hair, and then walk along the seafront eating a prawn sandwich in a heavily seagull-populated area of the coast.

“The phrase “dark Satanic Mills”, which entered the English language from this poem, is often interpreted as referring to the early Industrial Revolution and its destruction of nature and human relationships.

This view has been linked to the fate of the Albion Flour Mills, which was the first major factory in London. Designed by John Rennie and Samuel Wyatt, it was built on land purchased by Wyatt in Southwark. This rotary steam-powered flour mill by Matthew Boulton and James Watt used grinding gears by Rennie to produce 6000 bushels of flour per week.

The factory could have driven independent traditional millers out of business, but it was destroyed in 1791 by fire, perhaps deliberately. London’s independent millers celebrated with placards reading, “Success to the mills of ALBION but no Albion Mills.” Opponents referred to the factory as satanic, and accused its owners of adulterating flour and using cheap imports at the expense of British producers. A contemporary illustration of the fire shows a devil squatting on the building. The mills were a short distance from Blake’s home.”

From Wikipedia (I admit it, I love Wikipedia): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/And_did_those_feet_in_ancient_time

Left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left right left?