‘Plymouth Sound’ is the name of the wide inlet around which the city of Plymouth is built, and essentially the reason for the existence of the city. But why ‘sound’? why not ‘bay’ or ‘straits’ or ‘harbour’? ‘Sound’ is one of those words, like ‘fret’ (see entry for April 9th), that has multiple meanings, each of which adds to the richness of the word. Sound: not only a noise, both uttered, made, or occurring and usually heard (though Bishop Barclay had some doubts…); sound as a sense of wholeness and solidity (your reasoning is sound, the timber is sound); sound as in deep (I slept soundly); then there is sound, as in to ascertain, to sound out, to test, to probe – and, specifically it seems, in relation to sounding the depth of water using a line, pole or, more recently, sonar.

The reason for these differing uses comes from the fact that the word has several etymological origins: the Middle English soun, from Anglo-Norman French soun (noun), suner (verb), from Latin sonus (The form with -d was established in the 16th century); Middle English: from Old English gesund (healthy), of West Germanic origin; related to Dutch gezond and German gesund; Late Middle English: from Old French sonder, based on Latin sub- ‘below’ + unda ‘wave’

I had thought this last origin was the reason for the choice of word, being based on the need to navigate a safe passage through the waters forming this area of coast, but then I found a further possible meaning: ‘A narrow stretch of water forming an inlet or connecting two wider areas of water such as two seas or a sea and a lake. Another name for Øresund from the Middle English, in turn from Old Norse sund ‘swimming, strait’; related to swim’.

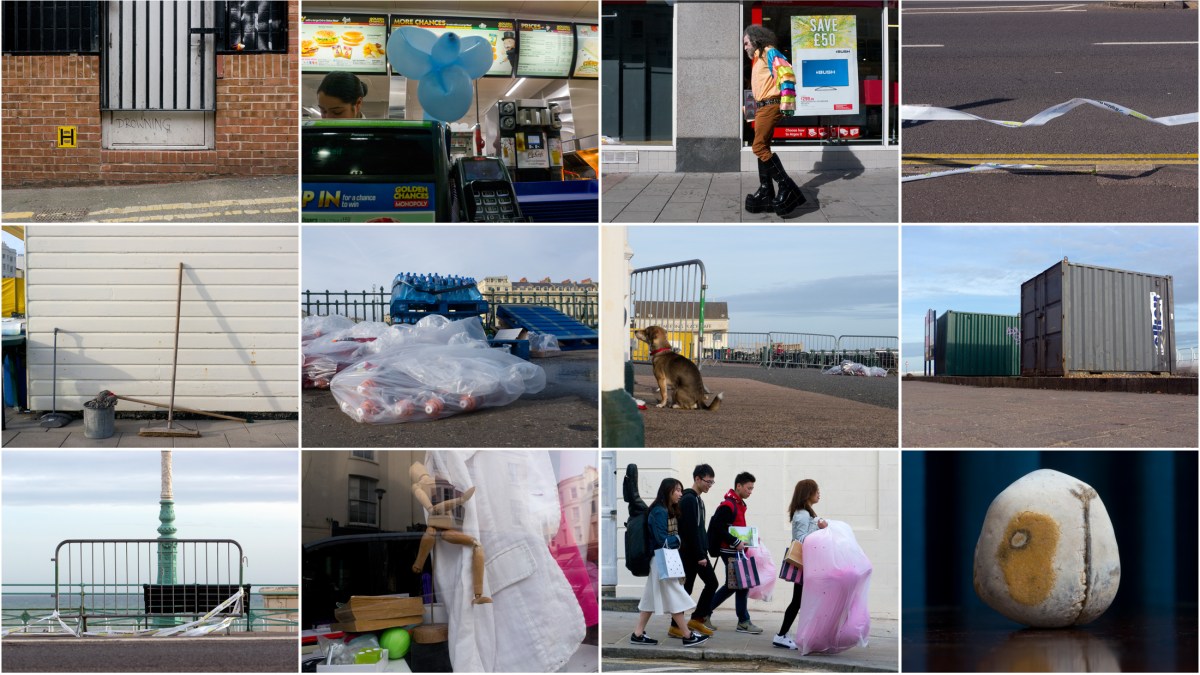

At first I was disappointed by this discovery. While this is most likely the reason, it seemed prosaic to name the place purely because of its geographical particulars. But then I thought, was it just because of this one definition? Perhaps whoever christened this stretch of water was well aware of the other meanings and it was a stroke of brilliance to use a name that could encompass so much.

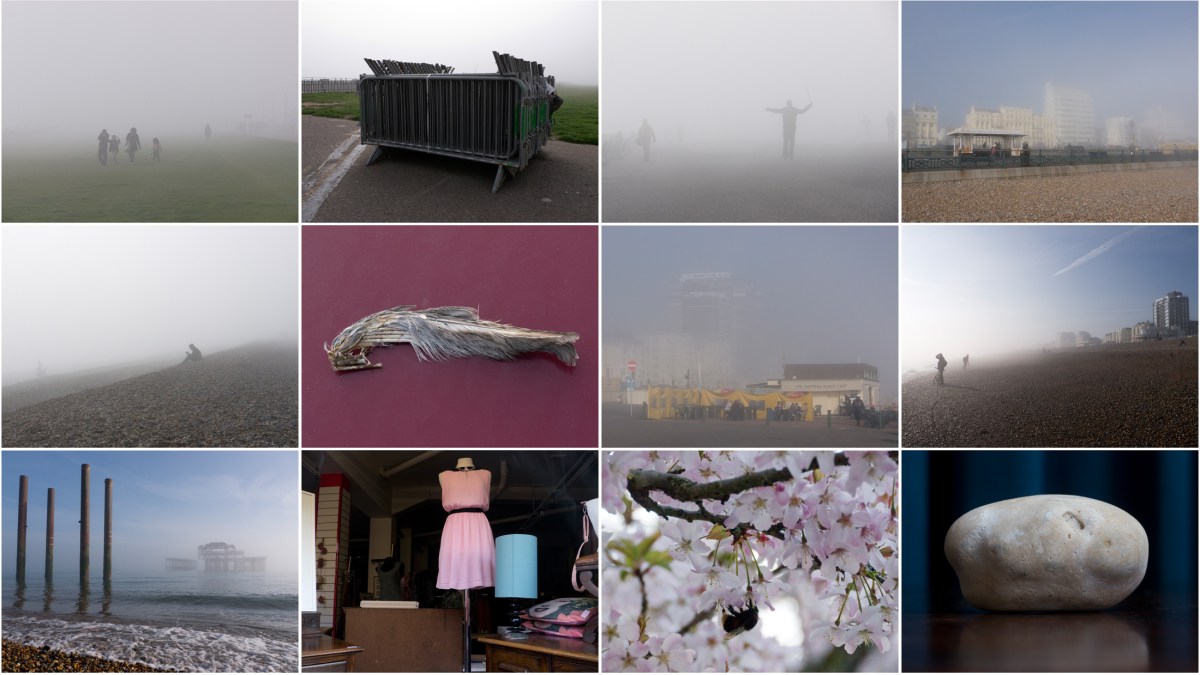

I was having a final cigarette on my last night in Plymouth, listening to the sound of the lapping waters magnified by the sea mist, when the stillness was punctuated by the great boom of an invisible ship off the coast. In that moment the name for this stretch of water seemed to capture, not only all that the word ‘sound’ could have stood for at the time of its naming, but what it would become centuries later.

Reference: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/sound